by Steve da Silva

Many of us have the impression that immigration policy in Canada is driven by so-called “Canadian values” like humanitarianism. This may have been part your or your parents Citizenship test, or maybe you learned this in school.

However, since the 1870s, Canadian immigration policy has primarily been about attracting workers to feed its expanding capitalist economy. In the century leading up to that, immigration policy was primarily focused on colonizing Indigenous lands with British settlers.

By 1942, just as most of Canada’s 23,000 Japanese were about to be branded as “enemy aliens,” dispossessed of their property, and removed to concentration camps, the government began thinking seriously about the crisis of legitimacy they would face after the war, especially in the eyes of non-Anglophone peoples. They did not want a repeat of WWI, which sparked the takeover of Winnipeg by workers in the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919.

In the same year, the Department of National War Services established an Advisory Committee on Cooperation in Citizenship that was charged with studying the views of immigrants for the purpose better cultivating their allegiance and loyalty.

Throughout the 1920s and ‘30s, a large section of the immigrant population and a growing section of the lower middle class were orienting towards the Communist Party and their vision for an egalitarian society; and communists played a leading role in building unions for industrial workers. So cultivating the allegiance of certain sections of labour in postwar Canada would be just as important as cultivating the allegiance of immigrants in general.

In February of 1944, the federal government passed an executive order recognizing trade unions; by March 1945, 133 new unions had been certified; and a fierce 99-day strike at Ford over the summer of 1945 led to the compulsory check-off of union dues from members’ pay cheques (the ‘Rand’ Formula, which is being threatened today). But these moves were not a concession to the communists: rather, bringing labour relations within the law went hand-in-hand with the subsequent policy of isolating and fiercely attacking communism during the Cold War period that followed.

In 1947, the Canadian Citizenship Act was passed, and in 1950, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent made clear that the goal of the Act was “to make Canadian citizens of those who come here as immigrants and to make Canadian citizens of as many as possible of the descendants of the original inhabitants of this country.” In other words, the objective was assimilation, for immigrants as well as for Indigenous peoples.

Once the flow of cheap European labour began drying up in the 1960s – the last waves of which were the Greeks and Portuguese – the Canadian state began looking towards other pools of immigrants, and to varying degrees grudgingly ‘tolerating’ non-white peoples migrating and gaining citizenship.

Canadian immigration policy responded to these labour needs by introducing the “points system” by 1967, which formally lifted the racial criteria (which identified “preferred races”) for immigration and set out ‘objective criteria’ for the recruitment of prospective immigrants, such as education background, language skills, occupation or professional experiences, as well as family ties to Canada. These policy shifts in immigration became institutionalized with the Immigration Act of 1976.

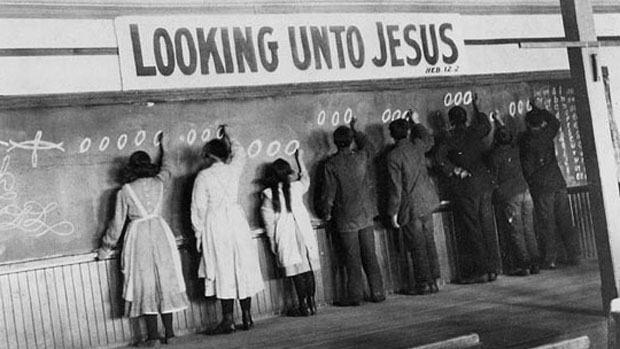

Meanwhile, the Department of Citizenship and Immigration (DCI) oversaw Indian Affairs from 1949 to 1966, at a time of the height of the Indian Residential Schools. A 1961 report from DCI explicitly stated that the government intended using off-reserve educational opportunities – such as the Residential Schools – as a means of depopulating reserves and effecting the assimilation of Indigenous peoples.[1]

By the mid-1960s, however, the Federal government became frustrated with the pace of assimilation of natives, and the Trudeau government decided to proceed with its infamous ‘White Paper’ of 1969, which called for a complete dismantling of the Indian Act and the direct assimilation of natives as ‘Canadians’ – which would have made them into the most dispossessed and poorest strata of the working class, and completely eliminated their self-determination.

The policy of native assimilation, the demand for cheap labour, and the need to tame Quebec nationalism, therefore, were driving forces behind the policy that we have come to know in the benign terms of multiculturalism.

But in his own day, Trudeau was clear that his policy of multiculturalism sought to “promote creative encounters and interchange among all Canadian cultural groups in the interest of national unity”. What national unity? Whose nation?

More people enter into Canada as temporary migrant workers than as permanent residents (Canadian Council for Refugees).

Many would point to Canada’s refugee policies (at least until very recently) as an example of Canada’s humanitarianism. However, as Pablo Vivanco analyzed in BASICS recently , it wasn’t until solidarity activists forced the Canadian government to accept Chilean refugees fleeing the Western-backed dictatorship that Canada’s refugee policy was partially opened up to refugees who weren’t anti-communist. Until the Chilean refugee crisis, Canada’s Cold War refugee system only granted asylum to people leaving ‘socialist’ countries, like Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Vietnam. Recruiting anti-communist refugees had a lot to do with national unity as well: the unity of Canada as a capitalist country.

With the banning of religious symbols in the public service in Quebec’s new Charter clearly directed at Muslims, many are wondering what happened to ‘tolerance’ in this country. But the emergence of the policy of ‘multiculturalism’ in Canada was never the product of some progressive enlightenment of Canada’s political system, its nationals, or its elites. It was developed in the postwar era as a strategy for the assimilation of immigrants, Indigenous peoples, and containing Quebecois nationalism. It was a policy for assimilating and managing an increasingly diverse population in the interests of capitalism and colonialism.

Many of us want to live in a diverse society where all peoples from all nations are genuinely respected and can fully participate in society for the benefit of all. But that was never Canada. Not yesterday, not today. That’s a society we have yet to build.

[1] See p.444 of Bohaker, H. & Iacovetta, F. (2009). Making Aboriginal people ‘Immigrants Too': A comparison of citizenship programs for newcomers and Indigenous peoples in postwar Canada, 1940s-1960s. Canadian Historical Review 90(3), 427-461.

Comments