by Nicole Oliver (photos by Alex Felipe )

“Detachment is not indifference. It is the prerequisite for effective involvement. Often what we think is best for others is distorted by our attachments to our opinions. We want others to be happy in the way we think they should be happy. It is only when we want nothing for ourselves that we are able to see clearly into others needs and understand how to serve them.” – Ghandi

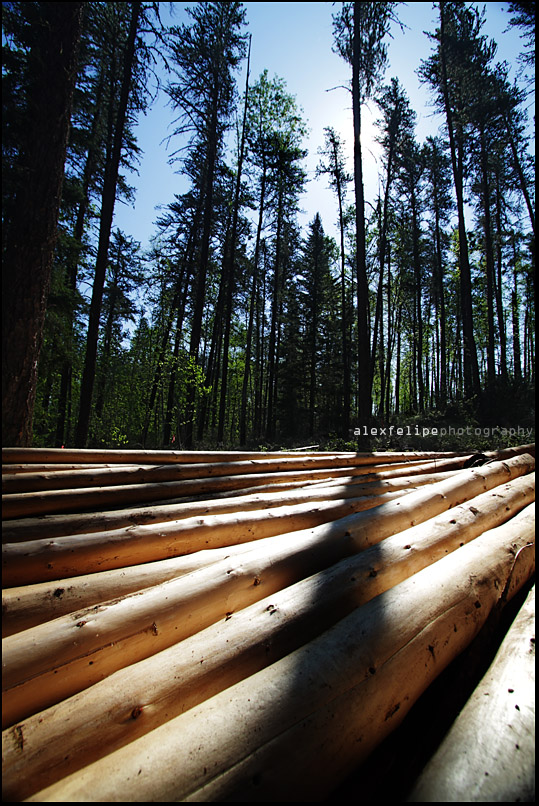

As a participant on the Biimadasahwin – ILPS Indigenous Commission cabin build project this quotation from Ghandi often enters my mind as I move from active participant in the building process to at times reflective observer of others and myself. Biimadasahwin means “life” in Ojibway . It is the name that Darlene Necan, a grassroots leader from the Ojibway Nation of Saugeen , has given to the project. This project has brought together community members from the Saugeen and individuals from various ILPS-Canada organizations such as Barrio Nuevo , Bayan , Basics , Binnadang-Migrante , CUPE 3903 , and the Revolutionary Women’s Collective . For many of us, myself included, engaging in grassroots work that combines intense physical labor, roughing it in the wilderness, and cross-cultural exposure to the Anishinaabe way of life definitely pushes our personal boundaries, taking us away from familiar understandings and ways of being. At times our patient and wise leader Darlene expresses frustrations with us as we try our best to learn and adapt.

Early morning, clearing debris from cabin site. The cabin is to be on left, the kitchen common area is on the right.

Sometimes as organizers, and I do not exclude myself here, we begin to think of ourselves as experts or as persons with particularized knowledge and lose sight of the fact that the community members whom we are working with are the experts in their own lives and communities. As community organizers in particular contexts our decision-making skills and responses to the challenges we face improve with experience. Due to the nature of our work many of these skills translate well into organizing in different contexts, but it is still necessary to recognize our boundaries and areas for growth as organizers when working in a new context, much like the cabin build project demands. Being overly confident in ourselves, our abilities, making assumptions, and not checking in with Darlene or the other Ojibway community members helping with the build while in the bush has resulted in setbacks and misunderstandings. For instance, one of the roles that I have been sharing responsibility for is that of cooking. Admittedly, there have been a few meals that I that I cooked a little too much to my taste regarding spice and heat. Upon reflection had I checked in with others regarding what they liked, especially given that food has both personal, cultural, and social elements attached to it, I would have been able to provide a meal that all could enjoy without wincing at the spice level. Thus, the bush and this type of work for myself reminds me to be humble, to check in with others, to respect the power of mother nature, and to listen to those who have walked these particular woods since they have taken their first steps.

So often as community organizers we are required to be active doers, leaders, initiators, and voices shouting to be heard. As we grow into the role of active doer and as our responsibilities increase with the demands of being an organizer, perhaps not enough space or time is dedicated to reflecting on our practices and our ways of being in community. Other times we dedicate too much time to conducting lengthy meetings, email exchanges, strategic planning, evaluations, and assessments; sitting around a table like a bunch of talking heads.

These issues in community organizing have also crept their way into the bush. One morning Darlene expressed impatience with us as our morning tasking meeting was pushing past brief. The other day when I showed Darlene my interview grid for an upcoming article that I wish to write about the trip, she exclaimed, “oh you people, why must you evaluate, assess, and dissect every little thing in such a way?” I think she was referring to how western academia has trained me to be so critical of every little thing, to overly categorize lived-experience into very structured and logical sequences, even that which is experiential and qualitative.

Prior trip departure, there has been a lot of time invested in planning, rapport building, fundraising, education, logistics and putting together a well-coordinated group of committed individuals. Given that much work went into the trip ahead of time persons most certainly arrived with opinions, personal expectations, goals, expected outcomes, and next steps. However, important preparation and planning are while engaging in the cabin build related work the need to be present, truly present in the experience should not be undervalued. Being truly present requires active listening and taking in the experience for just that, an experience in and of itself free of value judgments.

The need to be present and to actively listen in the bush can mean life and death. Time and again, as I work along side Darlene she points out the dangers of precariously hanging fallen trees, how to handle our tools, how to work together so we will not strain our backs, how to prepare the camp so that we will not be attacked by bears and other wildlife with which we share this environment. At times these constant reminders and Darlene’s mother-like watchfulness does cause some mild internal conflict for me as her directions collide with my own sense of self-sufficiency. When this happens respectfully I take a deep breath, actively listen and put my own sense of pride aside as her warnings come from a place of rich experience, deep care, and concern for those she is working with.

Being in the bush with Darlene on her family’s trap-line has taken many of us as organizers out of our comfort zones and away from the communities in which we typically organize. The transition from being a leader to being lead, from being a teacher to being a student, from being a voice to the active listener, I think is something that perhaps each of us at some point on this trip has had to confront. For some more than others being able to take a step back and to be open to being lead, to be open to being taught another way of doing and being has not been easy.

Much like the Ghandi quotation expresses there is much need here on the cabin build trip and in community organizing in general to put aside our own attachments, our own egos, our own desires, and needs to honor the needs of others. Despite knowledge and insights gained through our experiences as organizers we must allow ourselves to be humble and open-hearted to understand that people know their conditions, their lived experiences, their needs best and it is for us to listen to these needs and collectively organize around them.

Comments