By: Arthiga Arumansan

We go to school to learn right?

To become the big firemen we told our mothers

and the doctors that cared for the others

To learn about the world and what the amazing things it held

To grow our minds to think out side the box and the lines

To show that we are capable of excellence and beyond

And not what people said

to put us down

But why is it so hard now..?

Why is it so hard to get up these days

To detach from the lazy bed we laid

To do your homework and not get distracted

From social media that fed our curious minds about other peoples lives

That had nothing to do with mine

We started to call school stupid when other kids would die to sit in a desk and study about the old times

Because it didn’t become about learning anymore

it became about the marks

The big tests that we all look forward to get back

The exams we stayed up studying

Tryna memorize words one day before that wouldn’t be remembered

The notes we saw when you look up to the ceiling tryna think of the answers we got taught in december

Thats what started to matter..

We started to live for marks that showed up on thin sheets

that meant everything to parents

That grew their children to meet

To meet their expectations

That they thought their child didn’t receive

So they pressured their child to achieve.

This pressure never helped..

I wanna go back to the time when everything i learned amazed me

Not tired me

To the time when bedtime was at 8

But didnt sleep till ten

because I was too content

To when everything I learned only made me smarter

Not to learn how to memorize it in an hour

To when we were independent and didnt rely on people to bring in their papers

To when everything the teacher said became inspiring and something i felt proud to remember

But now

When we grew older..

Our bright goal to become a doctor has just became a thought to look back and remember.

]]>The University of Toronto and CUPE 3902, which represents student and contract teaching staff on campus, are currently negotiating new collective bargaining agreements. Negotiations seem to have stalled, however, and Units 1 (mainly TAs) and 3 (mainly sessional lecturers) are readying for a possible strike. At a townhall last Wednesday, BASICS caught up with two union reps.

Erin Black is the Chair of CUPE 3902 and the chief negotiator for Unit 3. Ryan Culpepper is the Vice-Chair for Units 1 & 2 and the chief negotiator for Unit 1.

Interview with Ryan Culpepper and Erin Black, 11 February 2015

BASICS: Is the University stonewalling you guys? I’ve talked to a few Unit 1 members, and it kind of sounds like that.

Ryan Culpepper: I think that’s fair, yeah. I think they’re doing the bare minimum that they can do and not run into trouble with the Ministry of Labour.

BASICS: And why do you think they’re pursuing that tactic?

RC: I don’t know, I mean—

Erin Black: They have claimed, and there is some truth to this, but how much truth is the question, virtually every unionised group on campus is bargaining this year, so they have been trying to kind of prioritise things or schedule things, and there’s only so many of them, uh, so they say. I have some—there is some truth to that, absolutely.

RC: Though they themselves negotiated the terms of the agreement, so like the fact they all expire in the same year is something that they themselves have set up.

EB: And they’ve known that we’ve been coming for three years, and could have, in my humble opinion, prepared for, better than they did, in terms of, ‘I’m sorry, we just don’t have any dates for you, ’cause we have to go talk to, uh, whoever.

RC: But right now they’re not meeting with us and there’s no other unions bargaining, it’s just us and they’re still not meeting with us.

BASICS: So most of the agreements have already been made, for the other unions.

RC: Yeah, the other two biggest are done, Steelworkers and another big CUPE local.

BASICS: So, in terms of [Unit 3] membership, there’s sessional Instructors, like Rank 1, Rank 2, Rank 3?

EB: Yeah we call it sessional lecturer 1, sessional lecturer 2, sessional lecturer 3, or SL 1, 2, 3.

BASICS: So how many people are in Unit 3 of CUPE 3902?

EB: Unit 3 represents approximately a thousand individuals, that’s sessional lecturers, writing instructors, we have some hourly paid employees who are musical professionals, but the bulk of the membership is sessional lecturers.

BASICS: And what percentage of the sessional lecturers would you say are SL1’s?

EB: Oh, the majority.

BASICS: And I think you said there were, 44–

EB: There were exactly 44 who have hit that brass ring of guaranteed work [this refers to SL3’s having guaranteed positions].

BASICS: And do you know how many SL2’s there are?

EB: You know what, if you give me a minute I actually ran these numbers for our bargaining team, if you give me a second.

[Reading from phone]: So there are 440 SL1’s, 120 SL2’s, and, sorry, 45 SL3’s, we have a new one this term.

BASICS: Moving up in the world. And so, the rate at which an SL 1 is paid per course is $7500?

EB: The SL1 is $7,125[per course], the SL2 is going to be…I can’t pull the exact figure out but it’s going to be around $7500, um, and SL3’s would be about $7900.

BASICS: And they are guaranteed four half-courses?

EB: Four, yep.

BASICS: No guarantee for SL2’s, but just preferred hiring.

EB: Just hiring preference.

BASICS: Is there a maximum, I don’t know if you mentioned this earlier, for the maximum number of courses—

EB: That you can teach? No. If you get to SL3 they owe you four; you can apply for work on top of that, and if you get it you can have it; but after 8 years of service, at least 8 years of service to the University, after having taught at essentially that course load, that 2/2 load, that’s how we refer to it, for at least 3 years, and after having been deemed ‘superior’ not once but twice, the university owes you what amounts to a gross salary of around $35 000. After all of the stuff you’ve got to get. And I might add, that commitment was not permanent, we successfully have achieved that in this round of bargaining. It was time-bound to each collective agreement, and in this round of negotiations they have now agreed to make it non-negotiable.

BASICS: Do you have a lot of people who are sessional lecturers for very long periods of time who aren’t moving up?

EB: We do, we have a classification called ‘SL1 Long-Term’, uh, so those people don’t have hiring preference but they get like a hundred bucks extra pay in honour of their at least six years of service to UofT.

BASICS: Do you have any idea how many people are in that category?

EB: That’s actually a small category, ’cause most people do advance, um, I think it’s probably about twenty or so who are at the long-term rank, most advance, but for—the reason some of these people, I’ve asked them, like, ‘you qualify for advancement, why don’t you do it?’ and the most common response I get back is, uh, ‘the process [of teaching review to be able to move up in level] is too intensive for the outcome; I have to go through all of these hoops, for what amounts to just a smidgen more pay, and a hiring preference, which is a good thing, but which may or may not matter because the course may not exist in the future anyhow.

RC: Also increasingly they’re screwing with the advancement process. Like, they’re denying more people advancement, and they’re doing weird things, like just as someone’s about to reach the threshold for an advancement review, they’ll pull their courses—

EB: ‘Oops, we don’t need your course this year!’

RC: —yeah, they’ll pull their courses so that they can’t reach the threshold to be reviewed for advancement.

EB: They’ll tell you that it was just, you know, curricular changes necessitating that.

RC: There’s lovely coincidences out there.

BASICS: Right, ‘changes in the historiography necessitate the end of your course.’

What’s the–do you have a rough idea of how many sessional instructorships there are offered in a year versus the new tenure track positions which would sort of, be offered? What would you say the ratio is?

EB: That’s a bit harder to answer. UofT is a little different than other institutions, so the growth rate of tenure-track positions—there was a study done by the Higher Education Council for Ontario…which investigated a bunch of universities in Ontario. At UofT, which is different than other institutions…there has been greater sessional growth than tenure growth, but UofT has also created a bunch of ‘teaching-stream’ positions, so full-time, permanent benefits, all that sort of stuff, represented by the faculty association, so those guys are higher than us, but less than the tenure-stream. And at other Ontario institutions…who aren’t doing this, it’s basically like, tenure [gesture to show tiny increase], sessional [gesture to show large increase]. But UofT has this weird sort of blip because of these teaching-stream positions that have been created, that are full-time positions; we’re thrilled to see them, [but] our long-serving members often don’t get hired into them; so you’ve created a teaching-stream position, and instead of affording it to the individual who’s been doing that work for five, six, seven, whatnot years, chances are it’s not going to go that person.

BASICS: So, these are full time positions, but they’re not professorships.

EB: Their rank system is ‘lecturer–senior lecturer’, but they are full time positions, they are continuing positions, they come with benefits and pensions and they are represented by the Faculty Association. But because they’re ‘teaching-stream’, they’re not ‘assistant, associate, full professor’, which has a much greater research requirement; so that’s the difference.

And then there’s us: the course-by-course-by-course.

BASICS: What’s the average TAship in terms of hours? How many hours is the average contract?

RC: Probably an average contract would be about 140 hours for a semester or 280 for a year.

EB: I can tell you in my department, for any incoming new student…they work very hard to make sure they do not get over the 205 hours [beyond which T.A.s are paid at the rate of $42.05/hour; under this threshold, their remuneration is considered to be made up by the $15 000 stipend which all PhD students receive]. This year I have two T.A.’s who were brand new students who were each capped at the 205.

BASICS: And that’s why they kind of start having contracts where you don’t have any remuneration for–

RC: Yeah they trim the hours so that they don’t have to pay you the hourly rate. When you get offered a job, you get offered a job that is for a certain number of hours. And then you have to sit down with the supervisor and go through the breakdown of the hours. So that’s where the process happens of saying, ‘you’re going to get so many hours for marking, so many hours for office hours–

EB: So many hours for actual class time.

BASICS: So this may be anecdotal, but in your experience, does it tend to be in situations where they’re trying very hard to make sure that a TA doesn’t get a contract for more than 205 hours, where they tend to have these, sort of, more brutal regimes where you don’t have any time to talk to students, where you don’t have any time to hold office hours, that kind of thing?

RC: Yeah, I mean, I don’t know how it is all over the university, I only know in departments where I’ve worked, I’ve seen big trimmings on contact time and prep time. That’s where they’re trimming back hours.

BASICS: And so, because course instructors are salaried, I assume there’s no–I don’t know, do you have an average of how many hours a sessional lecturer will spend working on a course?

EB: We did a survey of our members and asked that question; most said, if you were to add it up, the whole course, from start to finish, creation to delivery and marking and all that, most said that it’s probably at least 250 hours from start to finish. Interesting fun fact: for employment insurance purposes, a course is only credited at 230 hours.

And it really does vary. For instance I mentioned earlier, I teach a fourth-year seminar; because there’s no lecturing in that course, it’s straight up student discussion, and there’s fifteen students, it’s less labour-intensive than a course that I prepare lectures for. And the first time you’re preparing lectures for a course, it probably takes an average of maybe 8–10 hours to write one single lecture; so what gets spoken to the students in 2 hours takes probably 8–10 hours to actually draft. That first year I taught I actually kept track of my hours, and then I divided it by the stipend, and I was making below minimum wage. Because we’re not paid on an hourly basis; we’re paid like, ‘here’s a stipend.’ TA’s get this, Ryan referred to it, this Description of Duties and Allocation that breaks it down, x hours for this, x hours for that. I get a letter that says, ‘Dear Dr. Black, we’re hiring you to teach this, there are 24 hours of lecture in this course and one hour of office hours per week, and you will be paid x,’ which is the stipend, and x includes everything, from creating the syllabus, picking the readings, delivering the lectures, meeting with students, grading the students, or if I have TAs working for me, supervising the TAs—it’s kit and caboodle for them, it’s all part of delivering the course, so it’s one stipend.

BASICS: Can you tell us where the bargaining process is at?

EB: Sure. Both units are in similar spots actually; we’ve both filed for conciliation, which Ryan mentioned, that happened in December, we did it on the same day, that’s the process where you involve the Ministry of Labour. Both teams have now, after a meeting in conciliation, requested what’s called a ‘No Board’ Report, it’s a labour term basically. The upshot of that is when that report is issued, that starts a clock ticking, a 17-day clock, at the end of which puts either the union in a legal strike position or the employer in a legal lockout position. Both Units 1 and 3 have asked for the report that is now ticking down to a legal action on either side. But both have more dates to meet, [to Ryan] you have–

RC: Four.

EB: Four dates scheduled between now and the strike deadline, uh, the ticking clock ending, and we so far have the one additional date that they offered at 2 a.m. on Tuesday morning.

BASICS: And I guess in your experience, or in the experience of the union, is that–are four dates or one date a realistic amount of time to get an agreement?

That one’s harder to answer, I think what’s more telling is that Unit 1—what have you had now, a total of what, 14—maybe—dates? In the last round of Unit 1 bargaining [during the 2011–2012 school year], well before they even got to conciliation, they had like 25 dates.

RC: We had 18 even before our strike vote last time.

EB: Yeah, and this time there were like 6 or something. So it’s—at the end of things, processes can move or they can stall, that’s sort of amorphous, but—

RC: I mean, they know what it would take to get an agreement, right?

EB: Yes.

RC: They know what it would take to get an agreement, they’ve known since Day 1, so it could take one day, but that’s not the way that they bargain, so I mean, is timing a concern? Yeah, definitely.

BASICS: So, you mentioned the role of the province, the Ministry of Labour mediator, in the process, how helpful has that been? I don’t know what the specifics of that mediator role are.

EB: It’s up to the parties. So, sometimes the conciliator, he’s called a conciliator at this [earlier] stage, although now he’s a mediator, because both of us have filed the No Board Reports, he or she can do different things. Sometimes the parties sit in separate rooms and he or she shuttles back and forth, sometimes the parties meet face to face and the conciliator’s in the room, to sort of hear both sides, so it’s really up to the parties how they do it.

RC: And the Ministry of Labour employs conciliators in the first place for one purpose, which is to prevent strikes. That is their job. Their job is to prevent labour unrest in the province, so they come into the process, to sort of bash both sides on the heads and get them to come to an agreement. And so they go the employer and say, ‘Listen these guys are serious they’re gonna strike, you should be scared, give them what they want,’ and then they come to the union and they’re like, ‘Dudes they’re ready, they’re ready for you they’re gonna squash it you can’t go out you have to take the deal,’ like that’s their job, so you know. I don’t begrudge them for doing that job, but you have to recognise, I guess on both sides, what that is.

BASICS: I guess was just trying to get at—what kind of help from the province can you get, I mean, it doesn’t really sound like much if at all.

RC: I think the conciliator—the conciliators I’ve worked with in the past and our conciliator now, they’re usually quite aggressive, they really try to get you to make movement, draw proposals, that kind of thing. And that’s annoying and you have to develop your own way of dealing with them, but the good part is they also do that to the employer. I have found the ones I’ve worked with to be quite neutral in how they—all they want to do is prevent a strike, so they’ll be aggressive with both parties if it means, you know, getting you to sign a contract, so that is sometimes helpful.

BASICS: I wanted to ask about the solidarity between the two sections of the union: how did that come about, and is that rare, I guess? Do they often work together in collective bargaining? And also, it seems as though the University, if they’re closer to making a deal with Unit 3, then they might—is there a possibility that they would then use that against the TAs? Because it’s a lot harder to do a strike for just the TAs, right?

RC: Yeah.

EB: Well they’re a lot bigger though, I mean, much bigger, 6 000 to 1 000. So I think size takes away that sort of differentiality.

RC: I think it’d be more like, um, sessionals are—I mean, I’m learning from going out to events like this and talking to journalists, and sessionals are a more sympathetic crew; people like sessionals. So that’s great, um, so I think if sessionals [Unit 3] settled before we [Unit 1] did, I think the damage that it would do to us would be more like, ‘well, we always thought you were a bunch of unreasonable, radical students anyway, that nobody could deal with, and look, like the sane people, the people who will listen to reason settled; you’re on just some crazy crusade,’ and you sort of then lose the war of public opinion.

EB: I don’t disagree with Ryan, I think that would be the perception out there; what’s behind the scenes, though, is that for—[the University] are not making movement for Unit 1; they are making movement for Unit 3, and I’m not saying it’s enough—

RC: Oh yeah, fair enough, I think they’re absolutely trying to set themselves up to do exactly that, so that they can take, you know, frankly the more politicised Unit and give them a lot less, by giving some crumbs to the one that looks more sympathetic.

BASICS: But my impression is that Unit 1 is not asking for a lot—you said something like, a raise [to the guaranteed minimum funding package] of a few thousand dollars is not even going to put you above the poverty line—that doesn’t seem like an insane amount to—

RC: I don’t think it’s insane at all, but I think they would like to paint us as entitled, greedy—

EB: And what they’ll focus in on, and this is focused in on by student news coverage at UofT, is the $42.05/hour rate. Which is like, ‘Oh my God, you make that much? What are you complaining about?

RC: I did an interview with the Star today, and like, that’s all, I could not get her off the wage, that’s all she wanted to talk about.

BASICS: What would both of you want to say to people about the positions of your Units of the union?

EB: Well first of all, we are separate units, we have separate agreements, but we’re the same union, to come to your question about solidarity…we are CUPE 3902. So, we’re looking out for each other, to the extent that we can, we brought joint language, um, around common issues, which really freaked them out, ’cause this is the first time we bargained at the same time, normally it’s been one ahead of the other—

BASICS: So this is the first time that’s happened?

EB: Yeah, so that really freaked them out, and Ryan for Unit 1 came to the Unit 3 table, and they’re all like, [miming shock]—

RC: They spent an hour arguing whether I should be there or not.

EB: —it’s like, ‘what’s, what’s going on here?’

RC: They’re very very scared of the idea of collaboration. They said to me at that time, they said like, ‘You are the negotiator for Unit 1, how dare you try to bring that leverage to bear at this table!’ you know, like they are very scared of the idea of [collaboration]. I think the thing that is shared, and I hope it makes everyone equally sympathetic, but I’ll say this definitely about Unit 1 members, like I see, I’m out at info sessions and town halls all the time, and member department meetings, like, people are broke, they’re broke and they’re overworked and they’re exhausted and they’re exasperated, and the reason we are where we are is they feel like they’re out of options. So I think that’s shared with Unit 3.

EB: Oh it’s absolutely shared with Unit 3, equally as broke, equally as stressed. Have you heard of ‘Rhodes scholars’, right, like the impressive scholarship for Oxford, there’s a take on it, ‘Roads scholar’…because sessionals are always on the road so much, working at like a gazillion different campuses… One of our bargaining team members like goes to Peterborough for Trent, to teach. We have people who work on our campus who come in from as far away as London and Kingston and stuff like that. So yes, absolutely, the common ground is that whether you’re a graduate student education worker or somebody who has actually crossed the floor and gotten your PhD, we are similarly in the same economic boat.

BASICS: Living paycheck to paycheck.

EB: While being asked to do an incredibly important job, which is undergraduate education.

BASICS: What can students and the public do to mobilise or show solidarity?

EB: If the university can be told in no unequivocal terms, ‘We’re on their side,’ that’s going to be worrisome in Simcoe Hall.

* * *

You can follow updates from CUPE 3902 on Twitter at @cupe3902 or on their Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/CUPE3902

]]>Tensions are running high at the University of Toronto between administrators and CUPE 3902, the union which represents 7000 T.A.s and sessional lecturers on three UofT campuses.

During 2014, Units 1 and 3 of CUPE 3902 both had their collective bargaining agreements with the university expire. However, the University has shown little interest in negotiating new ones. In the face of intransigence from administrators, both Units have set a strike date of February 27. If collective bargaining agreements are not successfully signed by then, a large part of the teaching activities at UofT will temporarily cease.

A townhall held last Wednesday night at the George Ignatieff theatre, just south of Bloor and St. George, clarified the issues. Originally, it was organised as a forum for both CUPE and University representatives to explain their positions. A mere two days before the event, however, the University e-mailed organisers and notified them that it was refusing to participate. The peculiar reason provided was that “[negotiations] have not reached an impasse.”

This statement appears to bear little relation to reality. CUPE representatives Erin Black and Ryan Culpepper say that the University is resisting setting meeting dates on which both sides can negotiate.

“They’ve claimed [that] virtually every unionised group on campus is bargaining this year,” said Black in an interview, “[but] they’ve known that we’ve been coming for three years, and could have prepared better.”

Culpepper added: “But right now they’re not meeting with us and there’s no other unions bargaining. It’s just us and they’re still not meeting with us.”

Far fewer meeting dates have been set during this round of negotiations than in previous years. But so far it’s unclear why the university is uninterested in negotiating.

Empty chairs at empty tables: UofT representatives neglected to even show up on Wednesday.

Units 1 and 3 of CUPE 3902 are composed of different parties. Unit 1, with about 6000 members, represents mostly teaching assistants, who are almost all either graduate or undergraduate students at the University. Unit 3, with about 1000 members, primarily represents sessional lecturers.

Labour conditions for workers in both Units are no longer tenable. A minimum funding package for all PhD students at the University was won during the last CUPE 3902 strike in 2000, according to organisers. But this $15 000 per year stipend falls well short of the poverty line in this city, estimated at $23 000 per year.

“People are broke,” said Culpepper, “they’re broke and they’re overworked and they’re exhausted and they’re exasperated….they feel like they’re out of options.”

Despite inflation and rising tuition costs, it has been seven years since the last funding package increase. Furthermore, the package runs out after five years, forcing many students to search for other sources of funding. The goal of CUPE Unit 1 bargainers, therefore, is simply to get their members above the poverty line.

Sessional instructors, members of Unit 3, make on average about $7500 per half-year course they teach. If they manage to teach two courses per semester, which demands hours equivalent to a full-time job, they can make about $30 000 per year, plus a meagre $300 in benefits.

During the question period at the townhall, one speaker observed that the highest-paid person at the University (Jim Moriarty, who manages the UofT asset corporation) makes $750 000 per year, while President Meric Gertler, who because of his position has a residence provided by the University rent-free, makes over $400 000 per year.

Another student commented on the similar quality of instruction provided by sessional lecturers compared to tenured professors. She had taken a philosophy course one year from a tenured prof, and sat in on a lecture for the same course a year after, finding the experience “pretty much the same.” But, she pointed out, the University had to pay that professor almost $300 000 the year he taught that course, and only $7500 to the person who taught it a year later. “That’s not equal pay for equal work.”

The University’s media division did not respond when reached out to for comment.

]]>By: Aiyanas Ormond

On Tuesday, September 16, about 30 people picketed St. George’s, an elite private school in Vancouver. The picket, organized by Grassroots Women comes after more than 2 weeks of school closures as teachers in B.C. have been on strike.

St. George’s is the most expensive private school in the province with tuition ranging from $15,000 to $20,000 for non-boarded students and upwards of $50,000 a year for boarded students. The school boasts of its small class sizes, extensive supports and extracurricular programs, the exact things that public school teachers are saying are under attack with declining funding in B.C. public schools.

Grassroots Women, a working-class and militant women’s organization active in Vancouver since 1995, called for the picket to expose the fact that St. Georges also receives significant public funding, and to make the connection between the increasing number of students enrolled in publicly funded private schools and the economic starving of public schools, especially in working class neighbourhoods and communities.

“We’re picketing this school because, even though the tuition here is more than the annual income of tens of thousands of B.C. families, this school is subsidized from the public purse,” said Grassroots Women member Martha Roberts. “They receive 35% of the funding a public school would receive, per student enrolled – millions of dollars annually. And yet the sole purpose of this school, which is evident in reading any of their materials, is to replicate the economic power and class privilege of the families who can afford to send their kids here.”

It also happens to be the school where B.C. Premier Christy Clark sends her son. Her support for education privatization goes beyond her own personal preference though, British Columbia subsidizes private schools in the province to the tune of $300 million annually and has the highest number of children enrolled in private schools per capita of any province. B.C. also has the highest child poverty rate in Canada.

On the morning of the picket, the Province and teacher’s union announced a tentative agreement in contract negotiations that have been ongoing since public school teachers were left without a contract before the end of the school year of June 2013. “The union mounted escalating stages of labour action starting last April in an attempt to get movement from the employer at the bargaining table. After three weeks of rotating strikes, teachers launched a full-scale walkout about two weeks before the end of the last school year,” according to the Canadian Press. Thus, being on strike since the beginning of the current school year.

But the picket organizers were very clear that the issues of school privatization will not be resolved by a new contract for teachers.

“The public funding for private education is going to continue after this strike,” said Grassroots Women member Suzanne Baustad. “What we have is an increasing two-tiered system, one that is based on reproducing the next generation of bosses and bureaucrats on the one side, and workers on the other. This conflict really isn’t about government and teachers – its a class conflict, and redistributing resources from public to private schools is an attack on working class women and children.”

The action was the target of a significant online backlash, both from St. George’s parents, as well as from public school teachers and supporters, who were worried that militant action would “damage the teachers bargaining position.” An interesting reminder of how taboo it remains to engage in class conflict outside of the mediation of the State or the carefully scripted and managed collective bargaining process.

]]>

EARLY YEARS

O: I was born in El Salvador. My parents migrated here. I didn’t speak the language at all as a youngster, and I remember I was about 7 years old. You definitely feel outcasted. I remember feeling that the only people that really knew me and the only place where I felt safe was at home amongst my family. I would go to the classrooms. Kids would laugh at me.

R: The first school I went to, there was no ESL program at that school. There was one Latina. Actually she was from Spain, she wasn’t Latina, and she refused to speak to me. I remember very clearly that she said she would be considered low class if she was to speak Spanish to me.

RACISM

O: There was one particular incident where there were these two girls that were speaking and they were talking about my skin colour. Something along the lines that “We shouldn’t judge him because of his skin colour, like it’s not his fault.” And I was like “Really? Like why is that even a problem?” I didn’t even know that that was an issue.

R: I remember being picked on a lot. People would come to me and sing Daddy Yankee songs, like that was cool or that I would feel at home or something, and people bullying me. It was very hostile. A lot of people tried to fight me and I didn’t really know why.

At one point, I went to Mexico to celebrate Christmas. And so when I came back, the teacher had a set-up with chunks of desks, like she had four here, four there, whatever. And when I came back, my desk was at the corner closest to the door. And everyone else’s was at the opposite corner, packed away from me. And so when I walk into the classroom the teacher says to me, “Look, we just really feel you shouldn’t be here, because you’re Mexican and we don’t want to catch swine flu. And so we wanna ask you not to come back to school.” I got completely bullied. I was harassed. People wrote this on my Facebook and made videos about it.

SCHOOL

R: I got kicked out of the school because, well, I was in a classroom and the priest walked in and he started to ask people the commandments. And so I didn’t know them in English and so he threw a set of keys at me. And I picked them up and I walked to him and I gave them back to him in his hand. I mean, he was a priest and I was just coming from Mexico. And so he once more asks me for a commandment which I don’t know how to say. And so he throws the keys at me for the second time, and I pick up the keys and I throw them at him. And so I was like arrested [sic] by a teacher, and they took me to the office and they were just screaming at me. Like I understood what they were saying. They were saying I was stupid or I was gonna burn in hell, that Mexicans were violent, that it was all because I was Mexican. That Mexican people were horrible.

Then I arrived at Downsview which is where I completed my high school. There was a lot more Latinos at Downsview and things were a lot more enjoyable in the sense of students. I remember at one point we had a group of like 30 friends and we would help each other out. But as soon as I got there I was told by the principal that I would never be able to go to university, and that I would never achieve to graduate high school, because I would never be able to pass Grade 12 English.

And I was bashed out of many classrooms by teachers because I was called a communist, simply because I wanted to speak about things. I remember one time, this teacher wanted to give us a lot of homework for Thanksgiving. And I said to him, “No, this is a holiday.” And he started to argue to me and I said, “Look, this is not a dictatorship. You’re not an ultimate power. You are in a sense elected by somebody and if we all work as a collective and decide to walk out on you, you will be fired.” And he bashed me out of the classroom. He called me very nasty things and started to relate me to a lot of nasty characters in Latin American history. He started saying “Oh, don’t call Pablo Escobar on me,” and stupid things like that.

O: I remember this one professor, he was white, but I remember one of the first slides. He showed a little caricature, and he said, “Oh its scientifically been proven that those students that wear hats backwards, there is a correlation with lower grades.” So I purposely would bring in a cap. I wouldn’t always put it on backwards, but I would always bring it in, as a form of resistance. And you know, that’s bigotry right to the end because it’s based on absolutely nothing, and yet you’re claiming it to be scientific evidence, as a professor. I don’t know if he was joking but even if he was, like who jokes around about that? Why, out of everything, pick that? And I think that’s definitely targeting racialized groups. They don’t understand the culture that it even comes out of.

R: I was incarcerated [sic] by a principal. It was in high school and the teacher said we could do whatever we felt like doing, but our teacher had written on the board that we had to do a shitload of work, like a crazy amount of work. He had been absent and he hadn’t taught any of the material he wanted us to do, and so I was like “Wait a second, this guy never comes to class, never teaches the material and expects us to perform like a super student.” And so I said to the students “Look, if we all walk out of this classroom, the teacher can’t fail us all. If all of us get up and walk out right now, he’s screwed.” And so, we all got up… Well it took some convincing, took me a little more convincing. And so we all got up and started walking out, and the principal grabs me. Grabs me by the shoulders and yells, “Everybody get back into the classroom!” Everybody gets freaked out. Everybody started heading back in. And he says, “You’re coming to the office with me!” By the way, that class was very crucial to me. That was Grade 12 English and if I didn’t pass I wouldn’t graduate. And so he took me to the office and made me sit in a corner of his sketchy office. And so I said, “No, I’m an adult. You’re not gonna treat me like this. You’re not gonna segregate me, you’re not gonna outcast me because I was speaking about my rights.” And he was literally like, “Shut up, I don’t wanna hear you, go in your corner.” And so he locked the door and locked me in. And he left me in that office for two hours, just sitting there. And I remember kicking the doors and getting angry and screaming. I started writing step by step how I was segregated, and comparing it to acts of genocide which have happened in our society. Like I was locked in an office as a student for fighting for my rights! And I drafted this to the director of education. He looked at the paper and said, “Oh yeah, this is a good principal, don’t worry about it.”

At one point in my life, I was like, “Fuck this. These guys are all racist. I’m never gonna win against them. There’s no one like me. I’m a nobody. I’m not gonna go to university,” and I started believing it. And it’s really hard without teacher support, it’s really hard as a student. And it’s quite frustrating because you don’t have control over them. If a teacher wants to be racist to you, he will be racist to you. And to know that you can’t do anything about it, that you report it to the Director of Education and he does nothing about it. It’s frustrating. It’s heartbreaking.

You don’t feel like you belong in the school, all your teachers are white, and they talk about white behavior, and they’re all racist towards you, and it’s like well, what am I? A fucking alien? Am I the weird one? We talk about why there is so much violence in youth, why there is so much anger…fuck, what do you think this frustration builds to?

GENDER

O: I feel like a lot of times we have to resort to those things [violence], or fit into the stereotype that was being projected onto me. As a young Latin American male, you’re like cholo, gangster, like you have to do that. You have to be a drug dealer, beat people up, treat women like shit, be a scumbag, machista. Even with all the bullshit that we have to go through, I imagine it’s much, much more difficult for a Latina.

R: My girlfriend was told to take parenting classes five times because she was told by a guidance counselor that all she needed to do was go to university to find a husband. And that once she found a husband that what she would do for the rest of her life was be a mom, so she might as well take a lot of parenting courses. And so it took her two extra years to graduate high school because of that, because the courses she was supposed to take were not given to her because she didn’t need to be smart. All she needed was to find a good husband, so she was given almost a semester and a half of the same subject. Just because she was Latina.

LATINO COMMUNITY

R: There was definitely a lot of pride in the land where we came from and I never wanted to turn my back on mi gente and my community. I was blown away by the lack of community that I experienced here. Coming from a little colonia back home, it was all like one family and that was something that I lost. Every time you try to explain to people who we are as Latin Americans, we aren’t listened to. Like I feel that we are a minority and not even recognized…things like the constant need to remind people that we’re not Spanish but Latin American, and the constant need to remind people that we’re not all Mexican. We’re not all the same. It’s important for us to come together; I remember one of the chants in El Salvador that is used all over Latin America. “El Pueblo unido jamás será vencido” [The people, united, will never be defeated] and I truly believe that.

]]>On Jan 3, 2014, the Kitchener-Waterloo Spot Collective announced the relaunching and professionalising of their people’s programs.

The people’s programs, which include the serving of free food, programs for those dealing with addiction, and literacy programs, have come out of the need to deal with the problems the community faces by mobilising the community, says organizer Amber Sinson.

“Our children need food, warm winter clothing and basic needs that are not provided by the state,” Amber continues. “It’s obvious that we must rely on ourselves to solve our own problems.”

The Spot Collective, created in 1998 by street youth and socialist students looking for for solutions to the problems they were facing, has always focused on balancing the immediate needs of the community with solving the root causes of poverty by attacking systemic problems, according to Sinson. The relaunching of the people’s programs is a continuation of this combined approach.

When asked about food banks and other social agencies that provide such services she replied, “They humiliate you and make you feel like garbage, and that it’s your fault you’re poor. They also do nothing to address the issues behind poverty.”

Wesley Gibbons, a person who uses the peoples programs, also added, “You can only get one or two boxes a month from the food bank and most of the stuff is expired.”

Those interested in participating are invited to come out to meetings Wednesday nights at 6pm at 43 Queen St., after the free food servings. Contact: 226-289-2559.

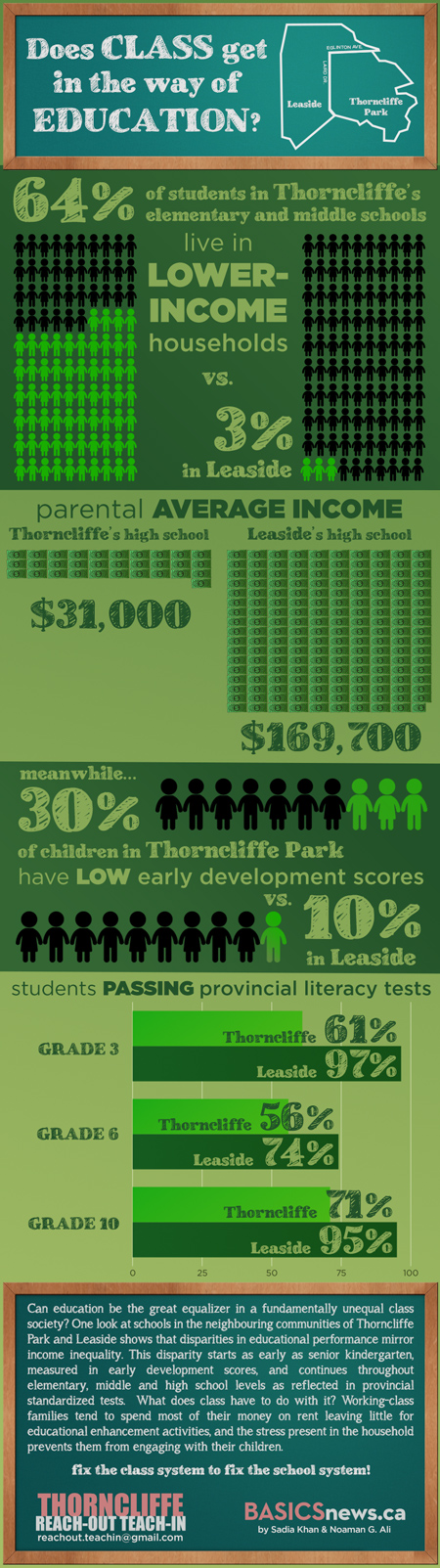

]]>Please see full article: Education inequality shocks Thorncliffe Park residents.

To get involved or to learn more about Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In (TRT)’s community organizing efforts to challenge these inequalities, e-mail [email protected], or visit the Facebook page, http://www.facebook.com/ThorncliffeRT/

]]>by Noaman G. Ali

“It’s shocking! I am shocked!” said a parent attending a community meeting in Thorncliffe Park held last Sunday, December 22.

Sadia Khan, a teacher and organizer with the Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In group addresses parents and students about education inequality. (Photo: Azfar Zaheer)

She was responding to a presentation by Sadia Khan, a teacher and community organizer, about educational inequality between public schools in Thorncliffe Park and those in neighbouring Leaside—schools that are about ten minutes apart by car.

Over 30 parents, students and other community members attended the meeting, organized by Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In (TRT), about the causes of educational inequality and building community power through solidarity in order to address the issues that face the community.

Khan showed how nearly 75 percent of students who had taken the Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test (OSSLT) at Marc Garneau College Institute, the high school that serves Thorncliffe Park and Flemingdon Park, passed in 2012. In contrast, over 95 percent of students at Leaside High School passed. Marc Garneau has an overall Fraser Institute ranking of 5.4, whereas Leaside has a ranking of 8.3.

The inequalities are also present at elementary and middle levels. In Thorncliffe’s schools, 57 percent of students passed the standardized tests in 2012, whereas in Leaside’s schools, 95 percent of students passed.

In fact, Khan explained, these inequalities are even present at the junior and senior kindergarten levels—shocking all the parents and even students in the room.

When asked why these inequalities existed, there were two main answers from the room.

Parents and students of Thorncliffe Park. (Photo: Azfar Zaheer)

“Thorncliffe Park Public School is the largest primary school in North America,” suggested one parent. Marc Garneau is also notoriously overcrowded, so much so that there are not enough textbooks for students to take home. “Teachers spend more time keeping track of students than actually teaching them,” another parent noted.

The other answer was that most people were recent immigrants and so could not communicate in English. “I have to help many people fill out forms,” a student noted. “So I can see how many parents may not be able to understand the messages they get from school.”

While these may well be factors, Sadia Khan explained that the kinds of scores and test results seen in Thorncliffe Park were also found in other neighbourhoods with fewer recent immigrants, like Jane & Finch or Parkdale. All three are low-income communities.

“The main problem,” Khan explained, “is the income gap between Thorncliffe Park and Leaside.”

The average income of families whose children attend Marc Garneau is $31,000, which puts them below the poverty line. In contrast, the average income of families whose students attend Leaside is $170,000.

Low-income families tend to spend most of their money on rent, and the stress present in the household prevents them from engaging with their children. Governments tend to favour richer, whiter communities like Leaside, whose rich parents can also raise funds for school activities on their own.

Despite the promise of equal opportunity, the very real class inequality between wealthy and poor neighbourhoods means that working-class and racialized communities lose out. “The capitalist economic system is what creates inequality in the first place,” Khan explained.

Rubena Naeem, a mother and organizer with the Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In group talks to the meeting about parents’ organizing. (Photo: Azfar Zaheer)

“I have lived in Thorncliffe for ten years and both my children have gone through the schools here. Why are our youth falling behind?” asked Rubena Naeem, an organizer with TRT and coordinator of the Thorncliffe Mothers’ Group.

“As parents—and especially as mothers—we need to get involved to have our voices heard. Yes, we’re busy and often have little time—we mothers are the ones who get our children ready for school and prepare for their return and extracurricular Islamic schooling, we prepare everything as our husbands come home from work.

“We address our children’s issues, but only individually. We have to look out for everyone’s children, so let’s organize to collectively address these issues.” It’s for that reason that Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In organized the meeting.

One TRT initiative seeking to build community capacity is a weekly free tutoring program for students, with the condition that they give back to the program in the form of providing free tutoring for younger students. TRT is also organizing other groups and initiatives to raise political consciousness about why the community and its occupants are being held back.

Sabeeha Ishaque, a Grade 12 student at Marc Garneau and a TRT member, highlighted a student group she had launched at the high school named ‘Youth 4 Truth’, which meets weekly and invites guests to discuss political and social issues.

TRT organizer Arsalan Samdani summed up the stakes, “Private services are too expensive, while government programs either neglect our community or are occasional and unsustainable. We have to build community power, independent of the government and funding agencies.”

The Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In group also organized childcare for parents with younger children. (Photo: Azfar Zaheer)

To get involved or to learn more about TRT, e-mail [email protected], or visit the Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/ThorncliffeRT/

]]>After decades of under-funding to First Nations schools – with high dropout rates and an epidemic of youth suicide that can’t be disassociated with the situation in schools – last Tuesday, October 22, the Federal government tabled their First Nations Education Act that will give it more direct control over about 515 reserve schools under its control.

Bernard Valcourt, currently the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development for Canada, has been a Conservative loyalist and politician for almost thirty years, holding cabinet positions on and off since 1986. Whose ‘solutions’ will this man bring to First Nations?

Under the draft legislation, band councils would be allowed to operate schools directly – as many already do – or purchase services from regional or provincial school boards or the private sector. First Nations could also form education authorities that would oversee one or more schools in a region.

However, under the new legislation it would be the federal government that would set and enforce standards for schools on reserves (with the exception of Onkwehon:we nations that have established self-government agreements that cover education). The Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development will retain the power to take over a school or if an inspector finds problems.

What the draft legislation is not clear about are the funding levels that fall far below funding provided to provincial schools. Funding short-falls have been a principal factor in keeping the standards in First Nations schools far below provincially-funded schools.

A piece of Canada’s Economic Action Plan, the Federal Conservative government claims their aim to be “improving graduation rates for First Nations students,” but First Nations (Indian Act) leaders are already decrying it as a renewal of the colonial legacy, by giving the Feds more control with no guarantee of the desperately needed funding increases.

In an October 25 press release, Chief Patrick Madahbee of the Union of Ontario Indians said that “The proposed First Nations Education Act (FNEA) is about control and false accountability,” says Madahbee. “It is a colonial document and makes no attempt to close the gap on inequality in education.”

“Firstly, it gives our citizens, parents and students no say in their own education… This is the same mentality as the government-run residential school disaster that had a history littered with genocide and acts of inhumanity.

“Secondly, it ignores curriculum needs that experts agree are essential to the academic success of First Nations learners – curriculum that talks about our culture and beliefs, and an accurate account of our historical contributions.

“And thirdly, this government starts their so-called educational reform with a threat to First Nations that if they don’t meet Canadian standards they will be put under third-party management, despite the fact that First Nation schools are largely underfunded and are unlikely to meet standards set by other, better funded schools, for example, the school in Biinjitiwaabik Zaaging Anishinaabek (Rocky Bay First Nation) receives $4781 less per student than nearby provincially-funded Upsala School in the Keewatin Patricia District School Board.”

Final legislation is anticipated before the year’s end after “consultation” with First Nations (Indian Act) authorities.

]]>

“Education without Borders” banner from community demonstration (J. Lapierre)

By J. Lapierre

The right to education for children without status in Quebec comes with a $5,000 price tag.

This past July, the Quebec government shared a set of guidelines with Quebec school boards for dealing with children with precarious immigration status. While the guidelines expanded the number of children who could access free education, students without status are forced to pay $5,000 to $6,000 in school fees.

“The situation isn’t complicated” Jaggi Singh from Solidarity Across Borders told the crowd of people who had gathered outside an elementary school where a Montreal school board was holding one of its meetings.

“We want children to be able to access education no matter what their status is.”

It was the seventh time people had come to demand that the school board allow children without immigration status to be able to attend public school.

Some school boards have refused students entry if they do not pay the fees upfront.

“There’s a family with two kids in a school board in the east end. They tried to go to school, but they were refused. The same thing happened twice with families in a school board in the south shore.” said Singh.

Other school boards seem content to simply send a bill.

One of the speakers relayed that one of the commissioners at the meeting told her that “the parents can simply rip up the bill.” However, receiving the bills in the first place is unsettling for parents.

The group Solidarity Across Borders has encouraged parents to register their children and has offered to support who want to challenge paying the fees.

As the group of people outside began to discuss how to pressure the school boards and the minister of education, a representative from the board was sent to meet with the crowd. He quickly became upset seeing that people are organizing and he pleaded with the group to “wait for the results of the board meeting.”

“It’s been two years!” someone from the crowd shouted.

The Quebec government has been particularly slow on this question. Both the United States and the Ontario government were forced to confirm the rights of children without status to free public school education in the 1980s.

Solidarity Across Borders has been campaigning for over two years now. And parents began organizing many years before that.

Charging parents without immigration status, most of whom are working low wage, insecure jobs because of their lack of documentation, for the education of their child is outrageous and inhumane. This is just another example of governments in Canada and Quebec attempting to squeeze working people, especially those who are most vulnerable.

]]>