By: Aiyanas Ormond

On Tuesday, September 16, about 30 people picketed St. George’s, an elite private school in Vancouver. The picket, organized by Grassroots Women comes after more than 2 weeks of school closures as teachers in B.C. have been on strike.

St. George’s is the most expensive private school in the province with tuition ranging from $15,000 to $20,000 for non-boarded students and upwards of $50,000 a year for boarded students. The school boasts of its small class sizes, extensive supports and extracurricular programs, the exact things that public school teachers are saying are under attack with declining funding in B.C. public schools.

Grassroots Women, a working-class and militant women’s organization active in Vancouver since 1995, called for the picket to expose the fact that St. Georges also receives significant public funding, and to make the connection between the increasing number of students enrolled in publicly funded private schools and the economic starving of public schools, especially in working class neighbourhoods and communities.

“We’re picketing this school because, even though the tuition here is more than the annual income of tens of thousands of B.C. families, this school is subsidized from the public purse,” said Grassroots Women member Martha Roberts. “They receive 35% of the funding a public school would receive, per student enrolled – millions of dollars annually. And yet the sole purpose of this school, which is evident in reading any of their materials, is to replicate the economic power and class privilege of the families who can afford to send their kids here.”

It also happens to be the school where B.C. Premier Christy Clark sends her son. Her support for education privatization goes beyond her own personal preference though, British Columbia subsidizes private schools in the province to the tune of $300 million annually and has the highest number of children enrolled in private schools per capita of any province. B.C. also has the highest child poverty rate in Canada.

On the morning of the picket, the Province and teacher’s union announced a tentative agreement in contract negotiations that have been ongoing since public school teachers were left without a contract before the end of the school year of June 2013. “The union mounted escalating stages of labour action starting last April in an attempt to get movement from the employer at the bargaining table. After three weeks of rotating strikes, teachers launched a full-scale walkout about two weeks before the end of the last school year,” according to the Canadian Press. Thus, being on strike since the beginning of the current school year.

But the picket organizers were very clear that the issues of school privatization will not be resolved by a new contract for teachers.

“The public funding for private education is going to continue after this strike,” said Grassroots Women member Suzanne Baustad. “What we have is an increasing two-tiered system, one that is based on reproducing the next generation of bosses and bureaucrats on the one side, and workers on the other. This conflict really isn’t about government and teachers – its a class conflict, and redistributing resources from public to private schools is an attack on working class women and children.”

The action was the target of a significant online backlash, both from St. George’s parents, as well as from public school teachers and supporters, who were worried that militant action would “damage the teachers bargaining position.” An interesting reminder of how taboo it remains to engage in class conflict outside of the mediation of the State or the carefully scripted and managed collective bargaining process.

]]>Located near the border between Scarborough and East York near Dawes Road, George Webster Elementary School is touted by its officials and the Ministry of Education as being a “model inner city school” that addresses the needs of the neighbourhood’s ethnically diverse community and working class inhabitants.

For a model school, or any other school for that matter, George Webster Elementary has a surprising neighbour. Overlooking the school’s playground rests one of the city’s only remaining indoor shooting ranges.

The shooting range, located at 11 Gower Street, is an inconspicuous one-story building that bears no sign of its function, were it not for the sound of gunshots ringing out from its building. Although the shooting range has existed for some time in the neighbourhood, the changing face of the area means that its presence is increasingly unsuitable, considering how heavily the surrounding area is used by children. In addition to its proximity to George Webster School, a few metres behind the shooting range is a playground of an apartment building that is used daily by children.

The shooting range at 11 Gower St., with George Webster Elementary School behind it. Photo: BASICS Community News Service.

The shooting range has been undertaking a number of initiatives in an attempt to establish links with the community, including hosting a tour of the facility. This is not a surprise, given where it is located and the recent bylaw and zoning restrictions that have threatened its continued existence. On August 29th 2008, the Toronto City Council voted in support of a report entitled City-Based Measures to Address Gun Violence. A number of shooting ranges were shut down as a result of these measures, including one at Union Station, after a public uproar.

Within this report contained a number of measures to curb gun-related activities – except those conducted by the police. Buried in this report, however, is a clause that allows any existing shooting range to continue as usual, stating that “Any amendments to a zoning bylaw would apply only so as to restrict the establishment of new firearm related uses, and would not render existing firearm related uses illegal”. This allowed the shooting range on Gower Street to continue, regardless of the public’s concern for its existence. The city’s policy recommendations were soft-handed when dealing with shooting ranges beyond its immediate control, and they failed to consider the safety of working class communities and children when allowing these ranges to continue in such close proximity to schools and playgrounds.

A manager of a nearby apartment building told BASICS that “most of the members are ex-cops” attending the shooting range. If this is the case, the presence of the shooting range in this community only highlights the ways in which the police and ex-police are one of the primary actors that normalize the use of guns in poor and working class communities.

For the children that attend the school and play in its parks, the sounds of the shooting range serve as a reminder of the violence that is often directed at them, as gentrification continues its march into the East End, and pushes the working class further into the city’s margins. A shooting range like this would never be found straddling playgrounds in wealthier neighbourhoods like the Beaches or Parkview Hills.

Image from Google Streets.

Image from

]]>

EARLY YEARS

O: I was born in El Salvador. My parents migrated here. I didn’t speak the language at all as a youngster, and I remember I was about 7 years old. You definitely feel outcasted. I remember feeling that the only people that really knew me and the only place where I felt safe was at home amongst my family. I would go to the classrooms. Kids would laugh at me.

R: The first school I went to, there was no ESL program at that school. There was one Latina. Actually she was from Spain, she wasn’t Latina, and she refused to speak to me. I remember very clearly that she said she would be considered low class if she was to speak Spanish to me.

RACISM

O: There was one particular incident where there were these two girls that were speaking and they were talking about my skin colour. Something along the lines that “We shouldn’t judge him because of his skin colour, like it’s not his fault.” And I was like “Really? Like why is that even a problem?” I didn’t even know that that was an issue.

R: I remember being picked on a lot. People would come to me and sing Daddy Yankee songs, like that was cool or that I would feel at home or something, and people bullying me. It was very hostile. A lot of people tried to fight me and I didn’t really know why.

At one point, I went to Mexico to celebrate Christmas. And so when I came back, the teacher had a set-up with chunks of desks, like she had four here, four there, whatever. And when I came back, my desk was at the corner closest to the door. And everyone else’s was at the opposite corner, packed away from me. And so when I walk into the classroom the teacher says to me, “Look, we just really feel you shouldn’t be here, because you’re Mexican and we don’t want to catch swine flu. And so we wanna ask you not to come back to school.” I got completely bullied. I was harassed. People wrote this on my Facebook and made videos about it.

SCHOOL

R: I got kicked out of the school because, well, I was in a classroom and the priest walked in and he started to ask people the commandments. And so I didn’t know them in English and so he threw a set of keys at me. And I picked them up and I walked to him and I gave them back to him in his hand. I mean, he was a priest and I was just coming from Mexico. And so he once more asks me for a commandment which I don’t know how to say. And so he throws the keys at me for the second time, and I pick up the keys and I throw them at him. And so I was like arrested [sic] by a teacher, and they took me to the office and they were just screaming at me. Like I understood what they were saying. They were saying I was stupid or I was gonna burn in hell, that Mexicans were violent, that it was all because I was Mexican. That Mexican people were horrible.

Then I arrived at Downsview which is where I completed my high school. There was a lot more Latinos at Downsview and things were a lot more enjoyable in the sense of students. I remember at one point we had a group of like 30 friends and we would help each other out. But as soon as I got there I was told by the principal that I would never be able to go to university, and that I would never achieve to graduate high school, because I would never be able to pass Grade 12 English.

And I was bashed out of many classrooms by teachers because I was called a communist, simply because I wanted to speak about things. I remember one time, this teacher wanted to give us a lot of homework for Thanksgiving. And I said to him, “No, this is a holiday.” And he started to argue to me and I said, “Look, this is not a dictatorship. You’re not an ultimate power. You are in a sense elected by somebody and if we all work as a collective and decide to walk out on you, you will be fired.” And he bashed me out of the classroom. He called me very nasty things and started to relate me to a lot of nasty characters in Latin American history. He started saying “Oh, don’t call Pablo Escobar on me,” and stupid things like that.

O: I remember this one professor, he was white, but I remember one of the first slides. He showed a little caricature, and he said, “Oh its scientifically been proven that those students that wear hats backwards, there is a correlation with lower grades.” So I purposely would bring in a cap. I wouldn’t always put it on backwards, but I would always bring it in, as a form of resistance. And you know, that’s bigotry right to the end because it’s based on absolutely nothing, and yet you’re claiming it to be scientific evidence, as a professor. I don’t know if he was joking but even if he was, like who jokes around about that? Why, out of everything, pick that? And I think that’s definitely targeting racialized groups. They don’t understand the culture that it even comes out of.

R: I was incarcerated [sic] by a principal. It was in high school and the teacher said we could do whatever we felt like doing, but our teacher had written on the board that we had to do a shitload of work, like a crazy amount of work. He had been absent and he hadn’t taught any of the material he wanted us to do, and so I was like “Wait a second, this guy never comes to class, never teaches the material and expects us to perform like a super student.” And so I said to the students “Look, if we all walk out of this classroom, the teacher can’t fail us all. If all of us get up and walk out right now, he’s screwed.” And so, we all got up… Well it took some convincing, took me a little more convincing. And so we all got up and started walking out, and the principal grabs me. Grabs me by the shoulders and yells, “Everybody get back into the classroom!” Everybody gets freaked out. Everybody started heading back in. And he says, “You’re coming to the office with me!” By the way, that class was very crucial to me. That was Grade 12 English and if I didn’t pass I wouldn’t graduate. And so he took me to the office and made me sit in a corner of his sketchy office. And so I said, “No, I’m an adult. You’re not gonna treat me like this. You’re not gonna segregate me, you’re not gonna outcast me because I was speaking about my rights.” And he was literally like, “Shut up, I don’t wanna hear you, go in your corner.” And so he locked the door and locked me in. And he left me in that office for two hours, just sitting there. And I remember kicking the doors and getting angry and screaming. I started writing step by step how I was segregated, and comparing it to acts of genocide which have happened in our society. Like I was locked in an office as a student for fighting for my rights! And I drafted this to the director of education. He looked at the paper and said, “Oh yeah, this is a good principal, don’t worry about it.”

At one point in my life, I was like, “Fuck this. These guys are all racist. I’m never gonna win against them. There’s no one like me. I’m a nobody. I’m not gonna go to university,” and I started believing it. And it’s really hard without teacher support, it’s really hard as a student. And it’s quite frustrating because you don’t have control over them. If a teacher wants to be racist to you, he will be racist to you. And to know that you can’t do anything about it, that you report it to the Director of Education and he does nothing about it. It’s frustrating. It’s heartbreaking.

You don’t feel like you belong in the school, all your teachers are white, and they talk about white behavior, and they’re all racist towards you, and it’s like well, what am I? A fucking alien? Am I the weird one? We talk about why there is so much violence in youth, why there is so much anger…fuck, what do you think this frustration builds to?

GENDER

O: I feel like a lot of times we have to resort to those things [violence], or fit into the stereotype that was being projected onto me. As a young Latin American male, you’re like cholo, gangster, like you have to do that. You have to be a drug dealer, beat people up, treat women like shit, be a scumbag, machista. Even with all the bullshit that we have to go through, I imagine it’s much, much more difficult for a Latina.

R: My girlfriend was told to take parenting classes five times because she was told by a guidance counselor that all she needed to do was go to university to find a husband. And that once she found a husband that what she would do for the rest of her life was be a mom, so she might as well take a lot of parenting courses. And so it took her two extra years to graduate high school because of that, because the courses she was supposed to take were not given to her because she didn’t need to be smart. All she needed was to find a good husband, so she was given almost a semester and a half of the same subject. Just because she was Latina.

LATINO COMMUNITY

R: There was definitely a lot of pride in the land where we came from and I never wanted to turn my back on mi gente and my community. I was blown away by the lack of community that I experienced here. Coming from a little colonia back home, it was all like one family and that was something that I lost. Every time you try to explain to people who we are as Latin Americans, we aren’t listened to. Like I feel that we are a minority and not even recognized…things like the constant need to remind people that we’re not Spanish but Latin American, and the constant need to remind people that we’re not all Mexican. We’re not all the same. It’s important for us to come together; I remember one of the chants in El Salvador that is used all over Latin America. “El Pueblo unido jamás será vencido” [The people, united, will never be defeated] and I truly believe that.

]]>On Jan 3, 2014, the Kitchener-Waterloo Spot Collective announced the relaunching and professionalising of their people’s programs.

The people’s programs, which include the serving of free food, programs for those dealing with addiction, and literacy programs, have come out of the need to deal with the problems the community faces by mobilising the community, says organizer Amber Sinson.

“Our children need food, warm winter clothing and basic needs that are not provided by the state,” Amber continues. “It’s obvious that we must rely on ourselves to solve our own problems.”

The Spot Collective, created in 1998 by street youth and socialist students looking for for solutions to the problems they were facing, has always focused on balancing the immediate needs of the community with solving the root causes of poverty by attacking systemic problems, according to Sinson. The relaunching of the people’s programs is a continuation of this combined approach.

When asked about food banks and other social agencies that provide such services she replied, “They humiliate you and make you feel like garbage, and that it’s your fault you’re poor. They also do nothing to address the issues behind poverty.”

Wesley Gibbons, a person who uses the peoples programs, also added, “You can only get one or two boxes a month from the food bank and most of the stuff is expired.”

Those interested in participating are invited to come out to meetings Wednesday nights at 6pm at 43 Queen St., after the free food servings. Contact: 226-289-2559.

]]>

‘Family Separation’- An art mural by Migrant Youth BC

by Jesson Reyes

In December 2013, the newly appointed Chris Alexander, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Canada, announced that the handful of proposed changes within the Family Reunification Program will be effective as of January 2, 2014. Together with this announcement is the assurance to the applicants of its main motives: to decrease processing time (currently averaging 4 years) and to clear backlogs in the application pool.

Most of the changes constitute an additional burden to what is already a challenging process to begin with: Citizenship Canada has been quoted as saying they are doing everything to reunite ‘families’ as quickly as possible. But the CIC defines a family as per the nuclear family model — family members that can come with you when you immigrate to Canada are your spouse, dependent child and the child of a dependent. Grandparents, siblings, cousins, aunts, and uncles are not allowed to be sponsored unless they are streamed into a particular program.

Also, an applicant who does not declare their “dependents” when they initially apply for the permanent resident form, will not be able to “add a dependent” in the future. This may not appear to be an issue for most applicants but it certainly affects those who may come from a particular situation where reasons for not claiming their children may come from the fear of persecution from either family members or their government.

The CIC’s definition of the family actually contradicts Statistics Canada’s, which in 2002 broadened its definition of family to include couples of any sexual orientation, with or without children, married or cohabiting, lone parents of any marital status, and grandparents raising grandchildren.

In addition, the age of who would be considered as a “dependent” will be changed from 22 to 19. It is important to remember that this particular change was considered to “better the economic integration” of dependents coming in to the country.

In 2012, Canada’s Economic Action Plan was released where the Government cited its immigration priority goals: to fuel economic prosperity, transition to a fast and flexible economic immigration system, and select immigrants that have the skills and experience required to meet Canada’s economic needs.

Research has demonstrated that older immigrants (age 19+) have a more challenging time fully integrating into the Canadian labour market, and so the policy is meant to promote immigration only of those deemed economically useful. The policy does not give consideration to family unity.

But one of the major barriers that those above the age of 19 face in finding jobs remains with the employers’ inability to recognize their working experience and/or their professional credentials. The Ontario Human Rights Commission even considers this requirement for ‘Canadian experience’ to be a violation of human rights. But the prevalence of such requirements leads to deskilling or deprofessionalization of well-qualified immigrants.

Clearly, Canada or at least its current government has demonstrated with its immigration policies that it is not willing to acknowledge and engage in the issues of transnational families. This is reflected in its reluctance to sign the United Nations Convention to Protect Migrant Workers and their Families. Canada has contributed to separating families through strict laws regarding migrant workers, since the 1920s with the Chinese railroad workers up until the introduction of the live in caregiver program in 1993.

All that matters is what is economically expedient, not family values! Statistics indicate that family class decreased from 43.9% of all immigration in 1993 to 21.5% in 2010.

Grassroots community organizations such as Migrante Canada, Filipino Migrant Workers Movement, Justicia 4 Migrant Workers, No One Is Illegal, and Migrant Workers Alliance for Change are all at the forefront of migrant struggles in Canada.

These groups are fighting both the injustices on foreign soil and against the systemic displacement of people through what countries like the Philippines call their ‘Labour Export Policy.’ Imperialist interventions and systematic underdevelopment provoke people to look for work abroad. The most important thing to keep in mind is that the struggles of migrants start way before they land on Canadian soil.

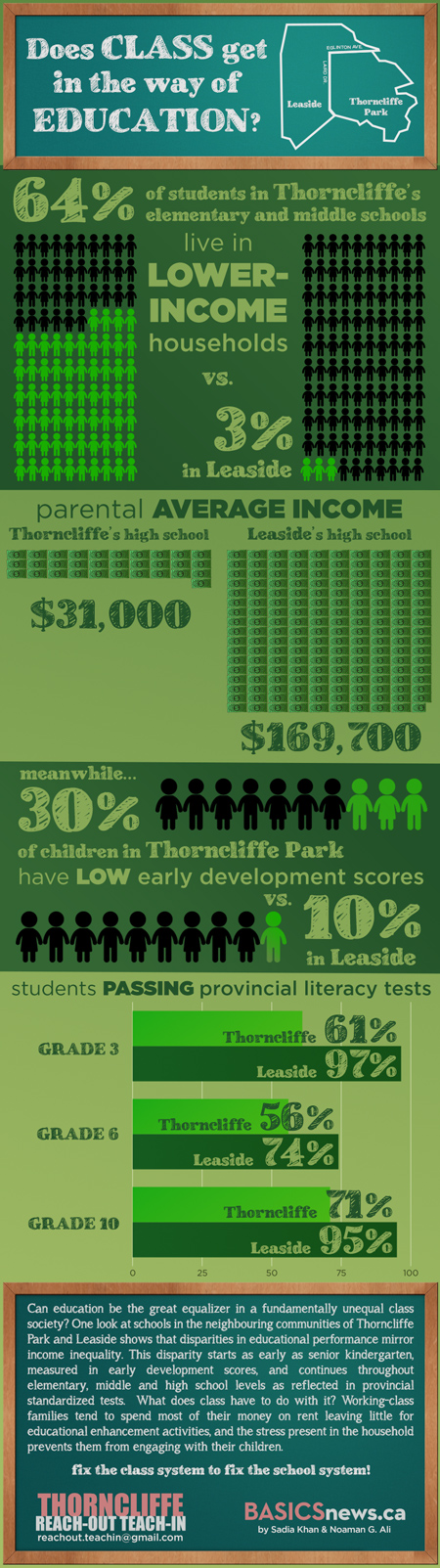

]]>Please see full article: Education inequality shocks Thorncliffe Park residents.

To get involved or to learn more about Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In (TRT)’s community organizing efforts to challenge these inequalities, e-mail [email protected], or visit the Facebook page, http://www.facebook.com/ThorncliffeRT/

]]>Kenneth Aldovino stood in the brittle cold after receiving an envelope from the mail this past 21st of January. The letter was disheartening: it was from Citizenship and Immigration Canada letting him know his permanent residence application had been denied, and he was asked to leave the country before the end of the month.

Aldovino has been in Canada for just six months. Edna Aldovino, his mother, had learned she had terminal cancer back in February 2011. Since her diagnosis, she had longed for her son, to be with him in her last days. But she was a live-in caregiver, faced with the choice of returning home or staying in Canada working to complete the requirements of her program before her son Kenneth could be eligible to join her. Mother and son spent only a week together before Edna’s passing in July 2013. And now Kenneth is being told to leave.

Edna Aldovino appearing with her son in 2011, before she migrated to Canada to be a Live-In Caregiver.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) policy states that the processing of Kenneth’s application stops with the death of his mother, the primary applicant. But Kenneth is asking for the right to carry on his mother’s residency application.

From 2009 to 2012, Edna came to Toronto to work in the Live-in Caregiver Program (LCP), wherein she sought to complete all the requirements to make her and her family eligible for Permanent Resident status. When she was diagnosed with a terminal cancer and needed to undergo chemotherapy sessions, she forced herself to continue working in the hope that she would complete the requirements. Most Canadian workers would have taken a leave of absence to focus on fighting the disease, but such ‘privileges’ are not afforded live-in caregivers like Edna, with their precarious legal and economic status.

The LCP exists to attract women’s labour – almost completely from the Philippines – to perform care work for the young and elderly at a wage and under conditions that many women in Canada simply would not tolerate. To qualify for permanent residency, live-in caregivers (LICs) must complete 3,900 hours or 24 months of authorized full-time work in the span of four years. In Ontario, they earn the minimum wage of $10.86 per hour and work 48 up to 56 hours in a week. Furthermore, living with their employers severely limits the privacy that live-in caregivers have, making them vulnerable to abuses such as working irregular hours and not having their overtime accounted for.

In case of a worker’s death, the CIC policy leaves sponsored dependents, mostly children, cut off from receiving what their parents struggled for. Unfortunately, Edna’s years of hard work and sacrifice will not fulfill their purpose of bringing Kenneth to live in Canada.

On January 27, an urgent meeting of migrant, refugee, and Filipino community groups agreed to campaign around the call to ‘Let Kenneth Stay’. Task Force Kenneth was formed to push for his right to the permanent residency that his mother earned. Letters of support are being collected; and online petitions are being circulated to encourage Canada’s Immigration and Citizenship Minister Chris Alexander to use his discretionary powers and allow Kenneth’s permanent residency application to be processed.

Having lost his mother so early in life, Kenneth will face great difficulty if forced to return to the Philippines where he will have no family and no financial support. In fact, thousands of young, educated Filipinos leave the Philippines every day for jobs abroad as a result of the country’s Labour Export Policy, which pushes its citizens out of the country to become highly exploited labour for imperialist countries like Canada. The lack of a viable and independent national industry in the Philippines is not only driving workers out of the country by the millions, the underdevelopment of the country further benefits corporations in the imperialist countries by having no domestic competitors to their exports to the Philippines. This is why women like Edna are forced to “tolerate” working conditions that many workers in Canada would not.

According to Anakbayan Toronto, a Filipino youth organization, there is a bigger issue at play in cases such as Edna’s: the lack of stable status accorded to workers under the Live-In Caregiver Program. Since caregivers are seen as a source of “temporary work” and not as immediate candidates for citizenship, these workers must migrate to Canada alone, undergoing a complete separation from their families.“The Labor Export Policy, pushed my mother to leave the country for a better job and has since continued to force 5,000 Filipinos everyday, as the lack of national industrialization has created unemployment and high underemployment in the country” stated Rhea Gamana, Chairperson of Anakbayan Toronto.

Edna is one of the several thousands of citizens who migrate abroad every year seeking better salaries. She left home in 1999 when Kenneth was just five years old and worked in Taiwan, Kuwait, Singapore and Hong Kong before coming to Canada. In addition to the emotional strain of being away from one’s family, live-in caregivers undergo difficult working conditions, finding themselves on-call around the clock, as the needs of the elderly and of the young for whom they care do not end after an 8-hour workday. Such arduous labour takes a physical toll on the body after time, and it is not surprising to find that many caregivers, like Edna, eventually develop serious medical problems.

Denying Edna’s wish to see her son gain permanent residency renders her years of hard work and ultimate sacrifice – her loss of life – meaningless. The Live-In Caregiver Program must not inflict any more injustices on the Aldovinos and future migrant youth. It’s the least Canada owes to Kenneth after his mother’s sacrifice. Let Kenneth Stay!

]]>by Noaman G. Ali

“It’s shocking! I am shocked!” said a parent attending a community meeting in Thorncliffe Park held last Sunday, December 22.

Sadia Khan, a teacher and organizer with the Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In group addresses parents and students about education inequality. (Photo: Azfar Zaheer)

She was responding to a presentation by Sadia Khan, a teacher and community organizer, about educational inequality between public schools in Thorncliffe Park and those in neighbouring Leaside—schools that are about ten minutes apart by car.

Over 30 parents, students and other community members attended the meeting, organized by Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In (TRT), about the causes of educational inequality and building community power through solidarity in order to address the issues that face the community.

Khan showed how nearly 75 percent of students who had taken the Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test (OSSLT) at Marc Garneau College Institute, the high school that serves Thorncliffe Park and Flemingdon Park, passed in 2012. In contrast, over 95 percent of students at Leaside High School passed. Marc Garneau has an overall Fraser Institute ranking of 5.4, whereas Leaside has a ranking of 8.3.

The inequalities are also present at elementary and middle levels. In Thorncliffe’s schools, 57 percent of students passed the standardized tests in 2012, whereas in Leaside’s schools, 95 percent of students passed.

In fact, Khan explained, these inequalities are even present at the junior and senior kindergarten levels—shocking all the parents and even students in the room.

When asked why these inequalities existed, there were two main answers from the room.

Parents and students of Thorncliffe Park. (Photo: Azfar Zaheer)

“Thorncliffe Park Public School is the largest primary school in North America,” suggested one parent. Marc Garneau is also notoriously overcrowded, so much so that there are not enough textbooks for students to take home. “Teachers spend more time keeping track of students than actually teaching them,” another parent noted.

The other answer was that most people were recent immigrants and so could not communicate in English. “I have to help many people fill out forms,” a student noted. “So I can see how many parents may not be able to understand the messages they get from school.”

While these may well be factors, Sadia Khan explained that the kinds of scores and test results seen in Thorncliffe Park were also found in other neighbourhoods with fewer recent immigrants, like Jane & Finch or Parkdale. All three are low-income communities.

“The main problem,” Khan explained, “is the income gap between Thorncliffe Park and Leaside.”

The average income of families whose children attend Marc Garneau is $31,000, which puts them below the poverty line. In contrast, the average income of families whose students attend Leaside is $170,000.

Low-income families tend to spend most of their money on rent, and the stress present in the household prevents them from engaging with their children. Governments tend to favour richer, whiter communities like Leaside, whose rich parents can also raise funds for school activities on their own.

Despite the promise of equal opportunity, the very real class inequality between wealthy and poor neighbourhoods means that working-class and racialized communities lose out. “The capitalist economic system is what creates inequality in the first place,” Khan explained.

Rubena Naeem, a mother and organizer with the Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In group talks to the meeting about parents’ organizing. (Photo: Azfar Zaheer)

“I have lived in Thorncliffe for ten years and both my children have gone through the schools here. Why are our youth falling behind?” asked Rubena Naeem, an organizer with TRT and coordinator of the Thorncliffe Mothers’ Group.

“As parents—and especially as mothers—we need to get involved to have our voices heard. Yes, we’re busy and often have little time—we mothers are the ones who get our children ready for school and prepare for their return and extracurricular Islamic schooling, we prepare everything as our husbands come home from work.

“We address our children’s issues, but only individually. We have to look out for everyone’s children, so let’s organize to collectively address these issues.” It’s for that reason that Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In organized the meeting.

One TRT initiative seeking to build community capacity is a weekly free tutoring program for students, with the condition that they give back to the program in the form of providing free tutoring for younger students. TRT is also organizing other groups and initiatives to raise political consciousness about why the community and its occupants are being held back.

Sabeeha Ishaque, a Grade 12 student at Marc Garneau and a TRT member, highlighted a student group she had launched at the high school named ‘Youth 4 Truth’, which meets weekly and invites guests to discuss political and social issues.

TRT organizer Arsalan Samdani summed up the stakes, “Private services are too expensive, while government programs either neglect our community or are occasional and unsustainable. We have to build community power, independent of the government and funding agencies.”

The Thorncliffe Reach-Out Teach-In group also organized childcare for parents with younger children. (Photo: Azfar Zaheer)

To get involved or to learn more about TRT, e-mail [email protected], or visit the Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/ThorncliffeRT/

]]>

Letter to the Editor – 22 December 2013

Thanks Vanessa Alexander for the article “Unlicensed Childcare: The Problem or the Solution?”, and thanks to BASICS for delving into an issue that’s central to the economic and social life of working class women, families and communities. As parents of three children we have relied on institutional and regulated daycares, unregulated home daycares, and many informal childcare arrangements over seventeen years.

The social reproduction of human beings in our society, and the smaller subset of ‘childcare’, is heavily based on the exploitation and super-exploitation of working class women. The basic contradiction of our society is that it is based on highly socialized production, we mostly produce things together, as part of a social project that’s larger than any individual; but the surplus of what is produced is expropriated by a small capitalist class who monopolize that surplus and the power that comes with it. The (re)productive labour in our society is largely rendered invisible in the capitalist economy, but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t central to the functioning of the system. The (re)production of the working class becomes an added burden of exploitation – super-exploitation – shouldered overwhelmingly by working class women. Even though working class people spend our lives integrated in social production, we are told that the labour and cost of taking care of and bringing up children should be borne, privately, by the women who give birth to them. Working class women and families get just enough in wage and social wage to be able to survive and continue to work! And each new generation of workers available for exploitation in the capitalist economy is a ‘commodity’ that working class women and communities produce for the capitalists basically for ‘free’. This added burden of exploitation is compounded with added layers of oppression for Native women, poor women, especially poor racialized women, women who use(d) drugs, and women with a ‘mental illness’ all of whom face additional stigma and discrimination which puts them regularly into contact with the punitive arm of the State: social workers, welfare ‘fraud’ investigations, child apprehension, and cops.

Because the capitalists have created an economic system in which almost every working class person has to work a job to survive economically, but will not use the social surplus to provide high quality childcare for working class parents, we rely on all kinds of arrangements to try to ensure that our kids are in a caring, stimulating and supportive social environment when we are not with them. Vanessa Alexander points out that these arrangements often demonstrate the strength, beauty and resilience of working class communities. Mutual aid, neighbourhood social networks, and extended families – these are all things that are woefully undervalued in our society.

She also does a great job of condemning a government policy that could be used to undermine and even criminalize the childcare arrangements that working class women and families make by necessity, in the absence of a universal childcare program.

There are two things that we would like to add, however, that we don’t think are adequately addressed in her piece.

Although Vanessa Alexander points to the fact that many informal childcare arrangements are borne out of lack of affordable options, we must be careful not to valourize these arrangements: The strain on relationships when you are relying on an aging grandmother or auntie or an older child to provide unpaid childcare; the stress of leaving your kid in a less than desirable childcare arrangement because you have no other choice; the developmental and mental health impact of kids isolated and watching TV or playing video games (for example while both parents are at work on a ‘professional day’); the strain on relationships between parents when every minute of childcare is used to cover work and they never get a minute alone together. While defending our right to survive the childcare crisis in whatever ways we can and deem to be necessary, we must be cautious not to embellish the means we take to survive. That said, the Little Lemurs Parenting Coop that Vanessa is part of organizing seems to be creating the best possible option for parents and their kids in order to avoid the worst of the informal childcare arrangements.

Canada’s Live-In Caregiver Program plans to bring 17,400 more caregivers in 2014 alone. The LCP helps reproduce ‘neoliberal’ capitalism by creating a low-wage caste of super-exploited women to look after wealthier people’s children, while working-class families are left without accessible daycare. The LCP sources its labour almost completely from the Philippines, a country in which policies of imperialist globalization are pushing people off their land and holding back the development of local industry to meet the needs of the peoples of the Philippines.

The second is a closer look at the current childcare set-up in Canada. As of right now, the Live-in-Caregiver program is the de facto national childcare program for more affluent Canadians. This program, set to double its number next year to 17,500, brings mostly Filipino women to Canada to work for less than minimum wage providing childcare and domestic labour for children and elderly in affluent Canadian homes while facing separation from their own families and a difficult uphill struggle to ‘achieve’ Canadian citizenship. The program is functional for capitalism and imperialism on many different levels: taking advantage of the underdevelopment and oppression of the Philippines and propping up the labour-export economic strategy of the reactionary Philippine state; providing the rich with access to childcare which is high quality, flexible and completely under their control; and maintaining the myth of childcare and reproduction as a private responsibility of individual families.

We need to analyze the burden of our oppression and exploitation, and organize to fight for a brighter future. We need to organize around demands that expose the exploitative and oppressive nature of the current system and that reflect the needs and aspirations of our working class communities. The demand for a universal childcare system is a key starting point for this demand because it is so obviously needed and enjoys support of the majority of people who live in Canada. But it’s not the end point. Licensed daycare that currently exists may not reflect the full aspirations of our families for the social development of our children and we must radically improve the working conditions of our dedicated and skilled childcare workers; democratic community control of childcare centers and secure, adequate state funding will help address our concerns.

We need to analyze the burden of our oppression and exploitation, and organize to fight for a brighter future. We need to organize around demands that expose the exploitative and oppressive nature of the current system and that reflect the needs and aspirations of our working class communities. The demand for a universal childcare system is a key starting point for this demand because it is so obviously needed and enjoys support of the majority of people who live in Canada. But it’s not the end point. Licensed daycare that currently exists may not reflect the full aspirations of our families for the social development of our children and we must radically improve the working conditions of our dedicated and skilled childcare workers; democratic community control of childcare centers and secure, adequate state funding will help address our concerns.

While we celebrate the strength and qualities in our communities that allow us to adapt and survive in a hostile capitalist world, we should not make the mistake of thinking that our liberation lies in these survival strategies and mutual aid programs. Our bright future includes a world where the work of (re)production is valued and honoured, where childcare is socialized, and the social alienation families and children is overcome.

In Solidarity,

Martha Roberts and Aiyanas Ormond

]]>

Two children in the Little Lemurs Parenting Co-op that existed in the Jane-Finch community from January to July 2013. The two children remain very attached to one another, despite no longer being in the same co-op and only seeing each other every couple months.

by Vanessa Alexander – 6 December 2013

Unlicensed childcare: It sounds scary, right? That’s what the media and the Ontario Government would have you believe. In fact, unlicensed childcare is all childcare that happens when there is no license: when your neighbour looks after your daughter while you run to the store, or when grandparents look after grandchildren for the weekend. It’s not scary, or it doesn’t have to be, because this means your childcare will be as good as the decisions you make as parents. If you give your children to a neighbour who looks after a few kids for income, you make a decision based on what you know. You know that they are unlicensed, but you know that you can trust them with your children. That’s not a scary decision. The scary part is when you have absolutely no childcare options.

This is what is unaddressed in the Childcare Modernization Act, a new piece of legislation tabled this past week by Ontario’s Liberal government. Unlicensed childcare is not the problem; the problem is a serious lack of affordable, high quality childcare options. The deaths of three children in unlicensed childcare facilities in the GTA over the last year have been waved around on a banner for months, despite the fact that no causes of death were identified, let alone a clear link between the deaths and negligence on the part of the caregivers. Still this threat is being hung over the heads of parents who might consider putting their children in unlicensed care.

Many parents have opted for unlicensed options rather than a licensed childcare provider, and for many this was an informed choice they felt suited their families, given the lack of affordable daycare. I am one of those parents. Together with other parents, I formed a childcare cooperative where rather than exchanging money, we exchange our time. For every hour I spend caring for children in the coop (at a ratio of 2 children per 1 adult) I earn an hour of care for my child from another parent in the coop. I don’t have enough time to work full-time, but I manage part-time work in addition to ensuring that my child has quality childcare when I’m not there.

With licensed care available for only 22 percent of children under the age of five in Canada, unlicensed care is, out of necessity, a common choice for parents. Unlicensed caregivers are only checked when there’s a complaint so we know very little about the unlicensed care going on across the country. The only time we learn anything is when something goes terribly wrong, providing a very warped picture of this type of care.

The Ontario provincial government has been quick to write new legislation in response to an outcry from the media and childcare experts who supposedly fear for the well-being of our children, but in fact the well-being of our children, at least for now, lies squarely in the hands of us parents and the decisions we make. It’s time to start taking responsibility for ourselves. If the Ontario Government is responding to a childcare crisis by restricting the childcare currently available rather than helping to create more affordable, high quality childcare options, we are going to have to respond ourselves by forming cooperatives and supporting trusted unlicensed caregivers. So long as the various levels of government refuse to create a universal childcare program, unlicensed childcare is not a problem but a solution.

To learn more about how to create parenting cooperatives or about Little Lemurs Parenting Collective, contact community.parenting.movement[at]gmail.com.

]]>